The White House and Pentagon’s latest review of the Afghanistan and Pakistan theater finally met its low expectations. Sporadic peaks dot the barren landscape, noticeably the drop of “AfPak,” considered a derogatory term in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. Those reporters briefed by Secretaries Robert Gates and Hillary Clinton also fulfilled their journalistic duty, critiquing U.S. strategy and the sugary coating on top.

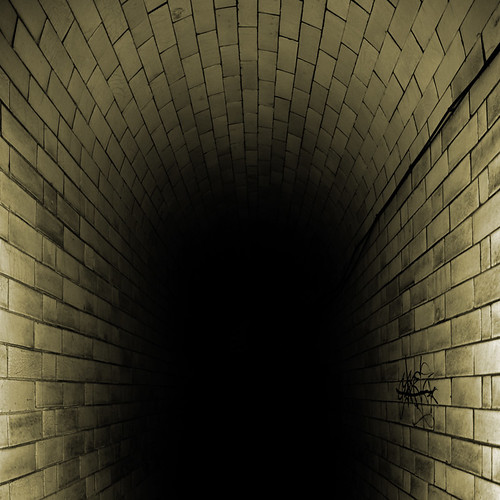

The White House and Pentagon’s latest review of the Afghanistan and Pakistan theater finally met its low expectations. Sporadic peaks dot the barren landscape, noticeably the drop of “AfPak,” considered a derogatory term in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. Those reporters briefed by Secretaries Robert Gates and Hillary Clinton also fulfilled their journalistic duty, critiquing U.S. strategy and the sugary coating on top.But contrary to the White House, Pentagon, and much of the U.S. media’s interpretation of Afghanistan, there’s no light at the end of this tunnel.

Three major strains of propaganda have infected Washington's latest review, all spawned from the “undeniable” progress of President Barack Obama’s military surge. First is the persistent hope that Obama will authorize troop withdrawals after July 2011. This false notion gives way to the perception that U.S. focus has “narrowed” on al-Qaeda rather than nation-building. As a result, even elements within the European media are talking up an “endgame” around 2014.

This chain of events sounds ideal for stabilizing Afghanistan. Unfortunately, it represents neither the real policy on the ground nor Washington’s practical intentions.

Goodbye July

To ascertain a clear view of the Obama administration’s strategy, a wary eye must first be cast on the July 2011 "deadline." Although one should never say never, all signs point to a minimum troop withdrawal through 2011. One anonymous official went so far as to suggest 20,000 soldiers could be redeployed without affecting combat operations. Nothing but pre-spin.

Obama didn’t deploy an additional 30,000 troops only to withdraw 20,000, 10,000, or even 5,000 at the war’s critical moment. And the Pentagon would block him if he tried.

The White House came prepared to negate this contradiction. The Taliban remains potent, Obama warned, but NATO operations have crippled its next offensive. This may be true to a degree, but U.S. intelligence still estimates the Taliban at 25,000 fighters. WikiLeaks also refuted U.S. claims of a cash-strapped Taliban through leaked Saudi finances. Nor is the Taliban’s morale weakening, as U.S. officials have argued by promoting false negotiations with its leadership.

The Taliban will hit hard in 2011, and America will need all 131,000 foreign troops stationed in the country.

Gates’s personal highlight came when he corrected Clinton for expressing indifference to U.S. public opposition, now at 60%. But he got his way in the end; no one is more sure of Afghanistan’s progress, and none more opposed to troop withdrawals. Wasting no time after Obama announced his 18-month deadline, the Secretary deployed his officials to attach a “get-out-of-promise-free” card: the infamous “conditions-based” withdrawal.

Repeated in the days after Obama's West Point speech and throughout 2010, today it was activated for good. No one mentioned troop levels, preferring to review the situation after next summer. Although Obama stuck to his time-frame during a brief statement, his overview foresees a “responsible, conditions-based U.S. troop reduction in July 2011.”

“In terms of when the troops come out, the President has made clear it’ll be conditions-based,” Gates added, transposing his own words into Obama’s mouth. “In terms of what that line looks like beyond July 2011, I think the answer is we don’t know at this point.”

Now Obama can renege on his promise without breaking it. Anyone expecting troop withdrawals over 1,000 are hoping at their own risk.

No Build, No Hold

Presuming that U.S. force levels will substantially decline after July 2011 leads to an even deadlier assumption: that Washington has sacrificed Afghanistan’s democracy and “narrowed” its objective to defeating al-Qaeda. Obama, Gates, and Clinton unified on this theme, each with their own twist. Obama credited his review and 18-month “deadline” for hastening the campaign against al-Qaeda, a sentiment echoed by Gates.

Obama claimed, “From the start, I’ve been very clear about our core goal. It’s not to defeat every last threat to the security of Afghanistan, because, ultimately, it is Afghans who must secure their country. And it’s not nation-building, because it is Afghans who must build their nation. Rather, we are focused on disrupting, dismantling and defeating al Qaeda in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and preventing its capacity to threaten America and our allies in the future.”

Yet contrary to Obama’s veto of nation-building, he outlines exactly that later in his remarks. The three areas of U.S. strategy, he says, remain “the military effort” to break the Taliban’s momentum, “our civilian effort to promote effective governance and development,” and regional cooperation with Pakistan. The latter two goals, and even parts of the first, are nation-building in nature. The first objective cannot be achieved without them.

According to David Galula, a founder of modern counterinsurgency, COIN isn’t addition but multiplication. Any one zero can take down a partially-completed equation.

Counter-terrorism has taken the lead over counterinsurgency - what some call a “militarized counterinsurgency” - not because Washington decided so, but because it had no other choice. Afghanistan’s political and economic spheres are lagging behind military progress, causing the White House and Pentagon to shuffle them aside in favor of military benchmarks. The goal remains as is: defeat al-Qaeda.

A “minimalist approach,” as Gates called it.

But Washington has been forced to avoid the politically radioactive term that is “nation-building” due to the absence of non-military gains: friction with Afghan President Hamid Karzai, faulty elections, prevalent corruption, proliferation of armed groups, a predominately Tajik army operating in the Pashtun homeland, and cultural ignorance in general. Make no mistake, Obama and Gates would have loved to lead with Afghanistan’s democracy. The Taliban cannot not be denied territory without better governance, thus al-Qaeda cannot be denied access.

And U.S. and Afghan forces would be running, as former UN envoy Kai Eide recently predicted, “clear and clear again” missions into 2014.

2014...2016...

Whether U.S. forces continue to militarily grind down the Taliban or shift to nation-building remains to be seen, but the next three years are likely to unfold in similar fashion. 2011 will mirror 2010's rough fighting, while 2012 and 2013, barring a negotiated settlement with the Taliban, are unlikely to decrease to a stable level. U.S. officials have already begun to preach “Afghan transition” to soften this harsh reality, and will enable an "annual" review cycle to limit public opposition until 2014.

But when the base crumbles it takes everything else down with it. Nothing more than a political scheme to minimize dissent, July 2011 has served to justify the war’s escalation and threaten Pakistan into invading North Waziristan. Significant delays in Marjah and Kandahar’s operations offered immediate visual evidence of future setbacks. As July 2011 melts into the slog between 2012 and 2014, the odds that America’s war will be winding down appear low.

For starters, 2014 isn’t designated as a withdrawal date but as a transfer date. 100,000 U.S. soldiers transferred control of Iraq to its military and police on January 1st, 2009, yet 50,000 remain in December 2010 and U.S. officials (including Gates) welcome an extension to the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA), which expires in December 2011.

Afghanistan's insurgency is also more complex and demanding than Iraq’s, meaning U.S. strategy doesn’t have a chance in Kabul if Washington expects to leave it like Baghdad. Just going by Iraq’s time-frame, Afghanistan's best case scenario pegs the complete withdrawal of U.S. forces at December 2016. Any time-line is automatically extended without a political settlement with the Taliban.

2018 doesn't scratch the surface of a worst case scenario.

Glaring Omission

Washington’s polarization of Afghanistan - negatives wrapped in positives - has amplified the war’s endless feeling. A Vietnam, treadmill-like feeling. However the unsaid also made its presence felt: al-Qaeda in Yemen (AQAP), Somalia, and North Africa (AQIM). U.S. officials now speak of these threats as equal to Afghanistan, yet the bulk of U.S. military resources is directed towards Afghanistan. As a result U.S. operations in al-Qaeda’s other strongholds are running on the cheap.

This isn’t to say they should increase, but that al-Qaeda has successfully adapted to its loss of Afghanistan.

Obama and Gates might have al-Qaeda "on the run" in Pakistan. Except it's running into other unstable lands and America is chasing again - exactly as al-Qaeda's grand strategy envisions. With the U.S. military already committed to two wars, al-Qaeda tied down America’s hands as it moved into new hosts, undermining Washington’s overall argument in Afghanistan. Can Washington multi-task against al-Qaeda’s safe havens or will the U.S. military, once it comes out of Afghanistan’s tunnel, be driven into another?

Such a critical question went unasked and unanswered today. It’s hard to see in the dark.

No comments:

Post a Comment